The Biological Revolution in Psychiatry Might Not Cut It

Written in November 2023

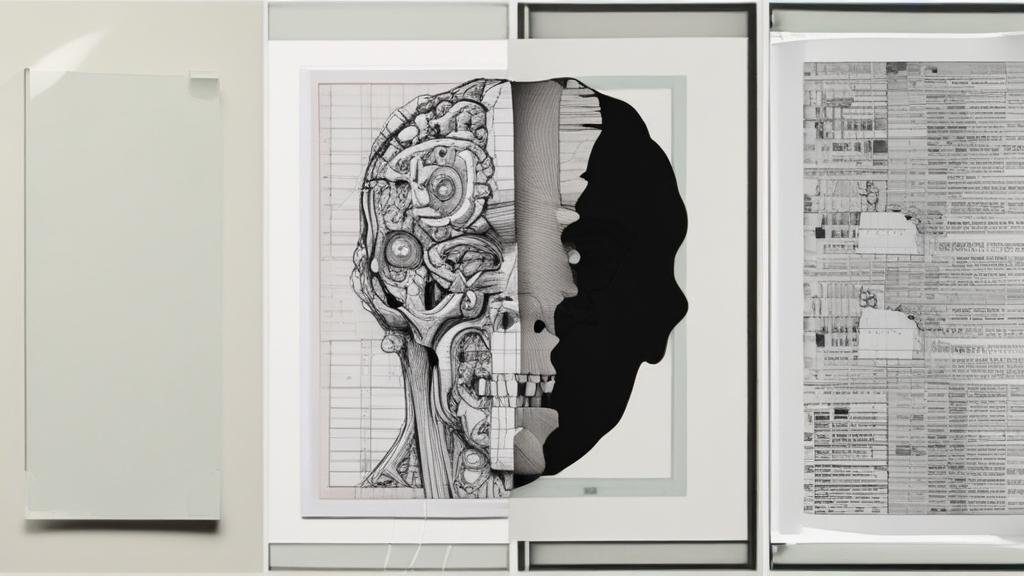

While the mental healthcare industry trends toward biology and genetics, some experts argue this approach doesn’t address the full picture

Written by ZACHARY HAYES

To many, the process of receiving mental healthcare is all too familiar: you visit a psychiatrist or a primary care physician, and after a brief, informal evaluation, they offer up a diagnosis, write you a prescription and send you on your way. Some mental healthcare specialists think we can do better. For the last decade, a new wave of psychiatric thought led by biological psychiatrists has been working towards a different reality, one in which mental illness would be diagnosed and treated based on biomarkers and brain scans. These researchers claim this new paradigm would be a more objective and scientific way to approach the practice of mental health, but many in the field say this purely medical model is missing the forest for the trees.

Much of the momentum for this biological movement stems from the 2013 publication of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5 — aka the bible of psychiatry — which the National Institute of Mental Health denounced in favor of a new approach they were creating. This new system, known as the Research Domain Criteria, or RDoC, would address the concerns of researchers who felt that the DSM-5, published by the American Psychiatric Association, didn’t go far enough in incorporating the latest research. RDoC builds on a broad range of state-of-the-art medical technologies — from neurobiology to genetics — that its developers believe will someday offer us a clearer picture of how and why we experience mental illness.

A medical model of mental health is by no means a new concept. Modern mental healthcare has been rooted in talks of brain chemistry and mental illnesses since the groundbreaking 1980 publication of the DSM-III, a revolutionary system that saw psychiatrists throwing out Freudian psychoanalysis for checklists of symptoms and diagnoses like Major Depressive Disorder. But while this system formed the basis of mental healthcare as we know it today, its roots in biology have been a source of controversy since its initial publication.

“Their main goal was to make psychiatry a respectable medical discipline,” says Dr. Allan Horwitz, author of “DSM: A History of Psychiatry’s Bible” and a Board of Governors Professor in the Department of Sociology and Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University. “Medical schools looked down on psychiatry and especially Freudian psychiatry. So they really wanted to put the field on a sound scientific basis where it would get a lot of respect in the medical schools in which they practice.”

While the architects of the DSM-III were steeped in the ethos of biological psychiatry, they realized the science simply wasn’t there yet, so in order to foster the appearance of a more empirical approach, they opted to base psychiatric diagnoses on groupings of observable symptoms instead. The science, they claimed, would reveal the biological origins in time.

“It became this sort of a theoretical monstrosity, but yet, it's this long, hardback, heavy book,” says Dr. Horwitz. “The very bulk of it makes it seem as if people really knew something about the conditions, whereas, in fact, it's a document that grew out of their ignorance of mental illness.”

Proponents of the RDoC system — and biological psychiatry in general — claim that the latest advances in medical imaging and genetic testing can now provide the science necessary to build a truly biological model of mental health, but experts in the field question whether this way of thinking will be able to account for all the complexities involved in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.

“The essential question is whether or not human behavior is somehow fundamentally different than human physical activity,” says Dr. Horwitz. “And of course, psychiatry can't accept that they would be fundamentally different because then they might not be medical at all. And that would be a real problem.”

In addition, many biological psychiatrists are rooted in heavily research-based institutions, far from the realities that many clinicians on the front lines feel are being largely ignored.

“I see it all the time with the people with schizophrenia that I work with,” says Kalea Barger, a study clinician working with the UMass Medical School’s Psychotic Disorder Research Program. “Only having a medical treatment causes so many issues in their health and their wellness.”

Barger, who also works as a registered behavioral technician with Surpass Behavioral Health, a practice that specializes in treating children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, argues that a purely medical approach to mental health treatment leaves out the important psychological, societal and interpersonal context that influences how mental illnesses arise and manifest. Ignoring this context, she says, limits the work clinicians can do to provide a more well-rounded treatment plan and potentially hinders a system of mental health diagnosis with stakeholders far from the clinic, including insurance companies, policymakers, and the criminal justice system.

“One way that it's restrictive in our clinic is that we have a lot of kids on this specific insurance that's really common around here,” says Barger. “And that insurance won't let us incorporate any academic learning into our clinic because it's not something listed as one of the bigger things that kids with autism will struggle with. I have kids who are high-support and low-support. And with the low-support kids, what else are we supposed to do? They can live independently, but they are struggling in school. But we're not allowed to technically do that, because we're only supposed to be treating the abnormal, unhelpful, dangerous behaviors that they're having.”

To combat this biological push in the industry, some mental healthcare researchers and practitioners are choosing to incorporate a wider array of perspectives into their work, a view that they hope will lead to a more holistic approach to mental illness.

“A number of people call it the biopsychosocial model,” says Dr. Horwitz. “It sort of says, ‘Look, mental illness is a complicated field, it has many different dimensions.’ There's certainly a biological aspect, but there's also a psychological aspect and a social aspect. People coming at this from different disciplines are going to emphasize one more than the other, but these are really more complementary kinds of perspectives than they are oppositional perspectives, so we need to understand all of these different perspectives to get a full understanding of mental illness.”

One interesting new approach — the community-based model — resurrects a way of thinking about mental healthcare that stems from the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, which aimed to create and fund a suite of community mental health centers across America to replace the country’s antiquated mental institutions. While this plan was shuttered due to Reagan-era budget cuts, the ideology behind it has experienced a resurgence in recent years with clinicians and practices offering mental health services beyond purely medical care.

“So much of the work we do at UMass is community-based,” says Barger. “Because people are multifaceted, and treating with only a medication isn't going to do anything to help their personal lives and their ability to live independently. Your goal should be, ‘how can I give this person what they need?’ Because we're not treating the categories, we're trying to treat the person. That just comes down to seeing as a whole, because you are also your community. And community, it's a big thing.”